History of the Assyrian people

|

The history of the Assyrian people begins with the rise of the Akkadian Empire during the 24th century BC, in the early bronze age period. Sargon of Akkad united all the native Akkadian speaking Semites and the Sumerians of Mesopotamia (including the Assyrians) under his rule. After the fall of the Akkadian Empire, the Akkadians split into two nations, Assyria in the north and later on Babylonia in the south. However, Babylonia unlike Assyria, was founded and originally ruled by non indigenous Amorites, and was more often than not ruled by other waves of non indigenous peoples such as Kassites, Hittites, Elamites, Arameans and Chaldeans.

In Biblical tradition, they are descended from Abraham's grandson (Dedan son of Jokshan), progenitor of the ancient Assyrians. However there is no historical basis for the biblical assertion whatsoever; there is no mention in Assyrian records (which date as far back as 21st century BC), andAssyria existed many centuries prior to the estimated birth of Abraham, circa 1800 BC.

The Assyrian king list records kings dating from the 23rd century BC onwards, the earliest being Tudiya, who was a contemporary of Ibrium of Ebla. However, many of these early kings would have been local rulers, usually subject to the Akkadian Empire. Assyria essentially existed as part of a unified Akkadian nation for much of the period from the 24th century BC to the 21st century BC, and a nation state from the 21st century BC until 605 BC. Assyria was for most of this period a powerful nation and had three periods of empire, between 1813–1754 BC, 1365–1076 BC and 911–608 BC.

Following the collapse of the Neo-Assyrian Empire and final resistance after 605 BC, Assyria came under the rule of its Babylonian brethren for a short period, until 539 BC. The last king of Babylon, Nabonidus, was ironically an Assyrian from Harran. Assyria then became an Achaemenid province named Athura (Assyria).[1] The Assyrian people were Christianized in the 1st to 3rd centuries,[2] in Roman Syria and Persian Assyria.[1] They were divided by the Nestorian Schism in the 5th century, and from the 8th century, they became a religious minority following the Islamic conquest of Mesopotamia. They suffered a genocide at the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, and today to a significant extent live in diaspora.

They are culturally, linguistically, and ethnically distinct from their neighbours in the Middle East – the Arabs, Persians, Kurds, Turks, and Armenians. Assyrian nationalism emphasizes their indigeneity to the Assyrian homeland, and cultural continuity since the Iron Age Neo-Assyrian Empire.

Contents |

Pre-Christian period

The history of ancient Assyria harks back to the Akkadian Empire of the Early Bronze Age. The Neo-Assyrian Empire flourished between 911BC and 608BC, before it was conquered by a coalition led by their Babylonian brothers which also included Medes, Persians, Scythians and Cimmerians . Linguistically, the Assyrians today speak dialects of eastern Aramaic, which was originally introduced to Mesopotamia in 1200 BC by large numbers of Aramean migrants who interbred with the native Akkadians. Aramaic became the lingua franca of the Assyrian Empire during Classical Antiquity.

After the defeat of Ashur-uballit II in 608 BC at Haran, and finally at Carchemish in 605 BC, the Assyrian empire was divided up by the key invading forces, the Babylonian Chaldean dynasty and the Medes. The Median empire was then conquered by Cyrus in 547 BC.,[3] under the Achaemenid dynasty, and the Persian empire was thus founded, which later consumed the Neo-Babylonian or "Chaldean" Empire. King Cyrus changed Assyria's capital from Nineveh to Arbela. Assyrians became front line soldiers for the Persian empire under King Xerxes, playing a major role in the Battle of Marathon under King Darius I in 490 BC.[4]

Achaemenid Assyria retained a separate identity for some time, official correspondence being in Imperial Aramaic, and there was even an attempted revolt by Assyria in 520 BC. Under Greek Seleucid rule, however, Aramaic gave way to Greek language as the official language. Mesopotamian Aramaic was marginalised, but remained the spoken language of the native population of Assyria,and indeed the whole of Mesopotamia.

Syria became a Roman province in 64 BC, following the Third Mithridatic War. The Assyrian army accounted for three legions of the Roman army, defending the Parthian border. In the 1st century, it was the Asyrian army that enabled Vespasian's coup. Syria was of crucial strategic importance during the crisis of the third century. From the later 2nd century, the Roman senate included several notable Assyrians, including Claudius Pompeianus and Avidius Cassius. In the 3rd century, Assyrians even reached for imperial power, with the Severan dynasty.

From the 1st century BC, Assyria was the theatre of the protracted Perso-Roman Wars. It would eventually become a Roman province (Assyria Provincia) between 116 and 363 AD, although Roman control of this province was unstable and was often returned to the Persians.

Early Christian period

Along with the Armenians, Greeks and Ethiopians, the Assyrians were among the first people to convert to Christianity and spread Eastern Christianity to the Far East.

Whereas Latin and Greek Christian cultures became protected by the Roman and Byzantine empires respectively, Assyrian/Syriac Christianity often found itself marginalised and persecuted. Antioch was the political capital of this culture, and was the seat of the patriarchs of the church. However, Antioch was heavily Hellenized, and the Assyrian cities of Edessa, Nisibis, Arbela and Ctesiphon became Syriac cultural centres.

The Council of Seleucia of ca. 325 dealt with jurisdictional conflicts among the leading bishops. At the subsequent Council of Seleucia-Ctesiphon of 410, the Christian communities of Mesopotamia renounced all subjection to Antioch and the "Western" bishops and the Bishop of Seleucia-Ctesiphon assumed the rank of Catholicos.

The Nestorian and Monophysite schisms of the 5th century divided the church into separate denominations.

With the rise of Syriac Christianity, eastern Aramaic enjoyed a renaissance as a classical language in the 2nd to 8th centuries AD, and the modern Assyrian people continue to speak eastern Neo-Aramaic dialects which still retain a number of Akkadian loan words to this day.

Islamic empires

The ancient Assyrian capital of Nineveh had its own bishop of the Church of the East at the time of the Arab conquest of Mesopotamia. The Arabs still recognised Assyrian identity in the Medieval period, describing them as Ashuriyun.[5] During the era of the Islamic Empire, Assyrians maintained their autonomy. The ancient city of Ashur was still occupied by Assyrians until the 14th Century BC massacres of Tamurlane.

Starting from the 19th century after the rise of nationalism in the Balkans, the Ottomans started viewing Assyrians and other Christians in their eastern front as a potential threat. Furthermore, constant wars between The Ottomans and the Shiite Safavids encouraged the Ottomans into settling their allies the nomadic Sunni Kurds in what is today Northern Iraq and South-eastern Turkey.[6] Starting from then Kurdish tribal chiefs established semi-independent emirates, those emirs sought to consolidate their power by attacking Assyrian communities which were already well established there. Scholars estimate that tens of thousands of Assyrian in the Hakkari region were massacred in 1843 when Badr Khan the emir of Bohtan invaded their region.[7] After a later massacre in 1846 The Ottomans were forced by the western powers into intervening in the region, and the ensuing conflict destroyed the Kurdish emirates and reasserted the Ottoman power in the area. The Assyrians/Syriacs of Amid were also subject to the massacres of 1895.

20th century

By the beginning of the 20th century, the Ottoman Empire was disintegrating. World War I and its aftermath saw its end, during which time Assyrians (and Armenians and Greeks) suffered the a genocide occurred (1914 to 1922), where an estimated two-thirds of Assyrians died in organized massacres, starvation, disease, and systematic kidnapping and rape.

Assyrians promeniently served in Iraq Levies organized by the British in 1919.

In 1932, Assyrians refused to become part of the newly-formed state of Iraq and instead demanded their recognition as a nation within a nation. The Assyrian leader Mar Eshai Shimun XXIII asked the League of Nations to recognize the right of Assyrians to govern the area known as the "Assyrian triangle" in northern Iraq.[8] Eventually this led to the Iraqi government to commit its first of many massacres against its minority populations (see Simele massacre).[9]

Post-Ba'thist Iraq

With the fall of Saddam Hussein and the 2003 invasion of Iraq, no reliable census figures exist on the Assyrians in Iraq (as they do not for Iraqi Kurds or Turkmen), though the number of Assyrians is estimated to be approximately 800,000.

The Assyrian Democratic Movement (or ADM) was one of the smaller political parties that emerged in the social chaos of the occupation. Its officials say that while members of the ADM also took part in the liberation of the key oil cities of Kirkuk and Mosul in the north, the Assyrians were not invited to join the steering committee that was charged with defining Iraq's future. The ethnic make-up of the Iraq Interim Governing Council briefly (September 2003 – June 2004) guided Iraq after the invasion included a single Assyrian Christian, Younadem Kana, a leader of the Assyrian Democratic Movement and an opponent of Saddam Hussein since 1979.

In October 2008 many Iraqi Christians(about 12,000 almost Assyrians) have fled the city of Mosul following a wave of murders and threats targeting their community.The murder of at least a dozen Christians, death threats to others, the destruction of houses forced the Christians to leave their city in hurry. Some families crossed the borders to Syria and Turkey while others have been given shelters in Churches and Monasteries. Accusations and blames have been exchanged between Sunni fundamentalists and some Kurdish groups for being behind this new exodus. For the time the motivation of these culprits remains mysterious , but some claims related it to the provincial elections due to be held at the end of January 2009, and especially connected to Christian's demand for wider presentation in the provincial councils.[1]

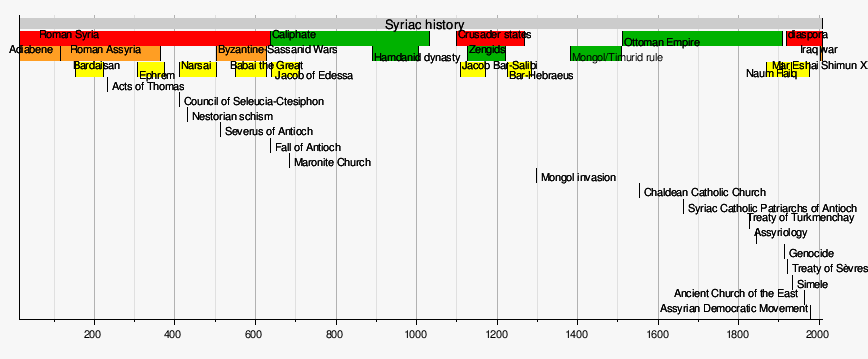

Timeline

|

|||||

See also

External links

References

- ^ a b "Assyria and Syria: Synonyms". PhD., Harvard University. Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 1992. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_KesgkBziUs. "The ancient Greek historian, Herodotus, wrote that the Greeks called the Assyrians, by the name Syrian, dropping the A and first S. And that's the first instance we know of, of the distinction in the name, of the same people. Then the Romans, when they conquered the western part of the former Assyrian Empire, they gave the name Syria, to the province, they created, which is today Damascus and Aleppo. So, that is the distinction between Syria, and Assyria. They are the same people, of course. And the ancient Assyrian empire, was the first real, empire in history. What do I mean, it had many different peoples included in the empire, all speaking Aramaic, and becoming what may be called, "Assyrian citizens." That was the first time in history, that we have this. For example, Elamite musicians, were brought to Nineveh, and they were 'made Assyrians' which means, that Assyria, was more than a small country, it was the empire, the whole Fertile Crescent."

- ^ Parpola, Simo (2004). "National and Ethnic Identity in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and Assyrian Identity in Post-Empire Times" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies (JAAS) 18 (2): 21. http://www.jaas.org/edocs/v18n2/Parpola-identity_Article%20-Final.pdf. "From the third century AD on, the Assyrians embraced Christianity in increasing numbers"

- ^ Olmatead, History of the Persian Empire, Chicago University Press, 1959, p.39

- ^ Artifacts show rivals Athens and Sparta, Yahoo News, December 5, 2006.

- ^ Hannibal Travis (2006), "Native Christians Massacred": The Ottoman Genocide of the Assyrians During World War I, Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal, vol. 1.3, pp. 329

- ^ Hirmis Aboona, Assyrians, Kurds, and Ottomans: intercommunal relations on the periphery of the Ottoman Empire, pp. 105

- ^ David Gaunt, Massacres, resistance, protectors: Muslim-Christian relations in Eastern, pp. 32

- ^ Islam and Dhimmitude: Where Civilizations Collide. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. 2002. pp. 148. ISBN 0838639437. OCLC 47054791. http://books.google.com/?id=PK-TPKvmG7UC&printsec=frontcover#PPA148,M1.

- ^ Iraq Between the Two World Wars: The Militarist Origins of Tyranny, by Reeva Spector Simon